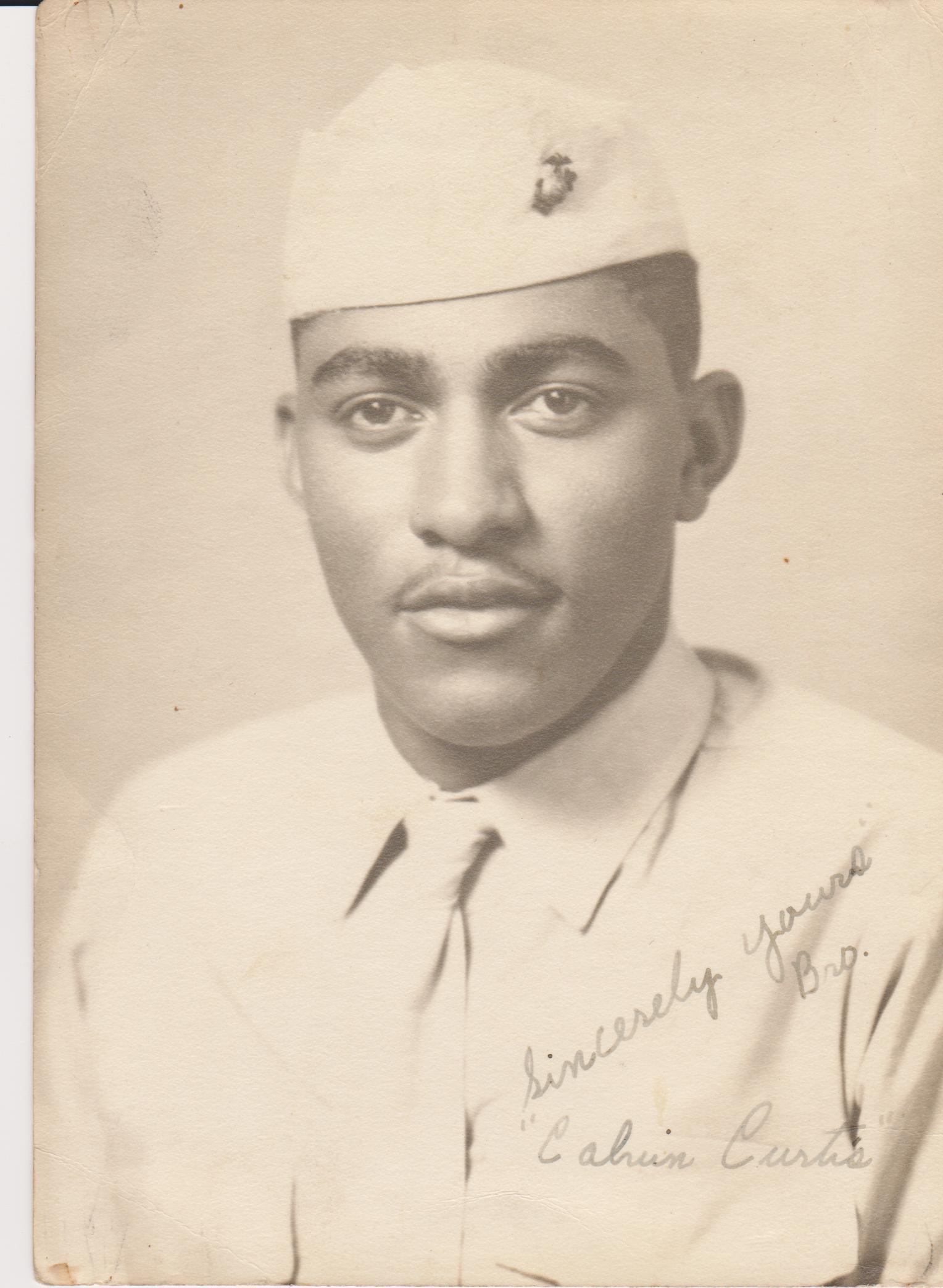

In memory of WWII veteran and Montford

Point Marine Calvin Turner Curtis Sr.

Calvin Turner Curtis Sr., World War II veteran and recipient of the Congressional Gold Medal, passed away on Wednesday, February 27, 2013 in San Antonio at the age of 87 following a short illness.

He was born May 17, 1925, in Charlotte, Texas, to the late Winfred Alexander Curtis and Minnie Turner Curtis. He was preceded in death by his wife of 55 years, Patricia Lucia Tennyson Green Curtis; by sisters Susie Hawkins and generic viagra online Margaret McKnight; by brothers Winfred Curtis, Lloyd Curtis, Emory Curtis, Everett Curtis, and his twin brother and fellow Montford Point Marine Clarence Curtis.

Calvin Curtis Sr. is survived by his three sons, Calvin Curtis Jr., Devon Curtis, and Dr. Todd Curtis; nine grandchildren who fondly knew him as "A-Da," and two great-grandchildren. He is also survived by his sister-in-law Nella Corbin of Columbia, Md., and by numerous nieces and nephews.

Calvin Curtis moved to San Antonio after leaving the Marine Corps in 1946. In 1949, he graduated from St. Philip's College in San Antonio, and began a 35-year career as a U.S. Postal Service letter carrier. Three years later, he married his wife Patricia on December 31st, 1952.

A committed community activist, Calvin Curtis was a member of several church and community groups�including the Neighborhoods First Alliance�helping to improve the lives of many. Over the years he also acted as local chapter president of the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees, was a historian for American Legion Fred Brock Post 828, and was a member of VFW Post 5142.

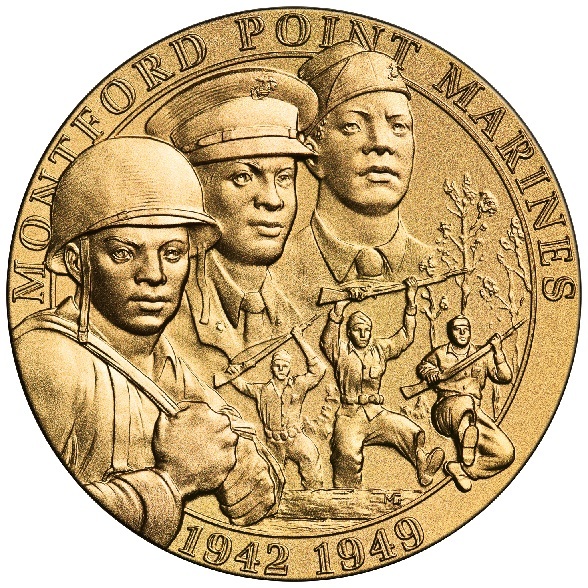

In December 2012, he was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal in recognition of his WWII service as a Montford Point Marine, the first African-Americans to serve in the Marine Corps since the Revolutionary War. A decades-long member of Jacobs Chapel United Methodist Church, he served there as a deacon, usher, and an enthusiastic member of the Men's Chorus.

Calvin Curtis Sr. was buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio. One of his final wishes was that in lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Jacobs Chapel UMC Scholarship Fund, 406 S. Polaris, San Antonio, TX 78203.

Presentation of Congressional Gold Medal to

Montford Point Marine and WWII

Veteran Calvin T. Curtis Sr.

On December 11, 2012, Montford Point Marine and WWII veteran Calvin T. Curtis was presented the Congressional Gold Medal, which is the highest civilian honor bestowed by congress for distinguished achievement.

The ceremony for Calvin Curtis was held on 11 am on December 11, 2012, and hosted by the 4th Marine Reconnaissance at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

The event was covered extensively covered by local news media.

On December 11, 2012, Montford Point Marine and WWII veteran Calvin T. Curtis was presented the Congressional Gold Medal, which is the highest civilian honor bestowed by congress for distinguished achievement.

The ceremony for Calvin Curtis was held on 11 am on December 11, 2012, and hosted by the 4th Marine Reconnaissance at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

The event was covered extensively covered by local news media.

Presentation of the Congressional Gold Medal

December 11, 2012

Broadcast from KABB Television in San Antonio

Other media accounts:

Express-News article #1

Express-News article #2

On June 27, 2012, the US Congress presented the Montford Point Marines with the Congressional Gold Medal. The medal was awarded to the Montford Point Marines in recognition of "their personal sacrifice and service to their country" as the first African-American Marines. Past recipients of the Congressional Gold Medal have included the Tuskegee Airmen; Dr. Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King; the Navaho Code Talkers, Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela, and Gen. Colin Powell.

House Speaker Boehner's Remarks at

Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony

Over 350 of the surviving Montford Point Marines were able to attend the ceremony in Washington, DC, receiving a significant public acknowledgement of their sacrifice and service. Below is a story about the life of one Montford Point Marine and WWII veteran Calvin Curtis.

Interview with Calvin T. Curtis Sr. from 2009

Jim Crow was loser in Korean War

On June 4, 2000, the San Antonio Express-News printed the following article featuring Calvin Curtis, a former U.S. Marine and African-American veteran of World War II. Calvin Curtis is the father of AirSafe.com Founder Dr. Todd Curtis

As a young boy growing up in the racially segregated South in the 1930s, Calvin Curtis always believed he and other African-Americans needed three things to overcome discrimination: money, education and a decent job opportunity.

World War II gave Curtis two out of three.

The San Antonian collected his first real paycheck after his first month of Marine Corps boot camp. When he completed his training, the Marines sent him to Hawaii, where he spent the rest of the war as an ammunition handler in an all-black unit.

It wasn't until the Korean War that the newly integrated armed forces gave African-Americans most of the same military opportunities as whites.

Curtis and his fellow black Marines worked mostly under the supervision of white officers and lived in their own camp, with their own barracks, mess hall and latrines during World War II.

"They didn't call it discrimination," he said. "But that's what it was."

John S. Butler, co-author of All That We Can Be: Black Leadership and Racial Integration the Army Way said America's need for troops for the Korean War helped create one of the most successful integration efforts in U.S. history.

"The military never set out to solve racial issues," said Butler, a professor of management and sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. "The purpose was to win wars and defend the country. Integration in the military had nothing to do with the issues of equality. The military's success has to do with keeping its eye on the prize."

Some historians have called the Korean War "America's first integrated war," although that label isn't strictly accurate. The first combined effort came during America's first war. Blacks and whites - in some cases, slaves and owners - fought side by side in the American Revolution as the need for manpower by the fledgling republic outweighed historic prejudices and practices.

After the fighting, it was back to segregation as normal. About 3,000 blacks fought for the United States in the War of 1812, despite an official prohibition against their service.

The Civil War started the same way, although leaders for the North - facing a manpower crisis late in the conflict - relented to demands and formed all-black units. They included the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, a black outfit commanded by white officers and later depicted in the film "Glory."

After one bloody battle left half of the unit's members - including its commander - dead or wounded, Confederate troops tossed the white officer's body in a grave and piled his dead black soldiers on top of him.

Segregation continued well into World War II. More than a million blacks served in that war, of the more than 16 million U.S. military personnel. Most were assigned to construction, transportation, service or support units.

Success stories

Despite some success stories, such as the 332nd Fighter Group

- the famed "Tuskegee Airmen," who never lost a bomber under their

escort to enemy planes - America's military leaders were reluctant

to put blacks in combat units.

Near the end of World War II, U.S. brass began reinforcing otherwise all-white companies with black combat platoons after the Battle of the Bulge threatened to turn the tide of the war against the Allies, who sustained heavy casualties in the victory.

"Part of it was a fear that - based on stereotypes of blacks - that blacks would be too afraid to fight and wouldn't be effective soldiers," said Philip A. Klinkner, an associate professor of

government at Hamilton College in New York and co-author of The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America

"The other sense was that if you're putting somebody on the line to fight for your country, it's really hard to deny citizenship rights."

As a result, many menial tasks fell to blacks in the military during World War II, just as they did back home in civilian life.

For example, after training at Montford Point, a segregated boot camp for black Marines at Camp Lejeune, N.C., Curtis spent two years loading and unloading heavy crates of small arms cartridges from ships, trucks and railroad cars in Hawaii.

Life for Curtis and his fellow soldiers was almost completely segregated, right down to their blood supply, to prevent complaints from white soldiers giving or needing transfusions.

Inevitably, prejudice created tensions that sometimes escalated into fistfights or worse. Curtis says he and some of his buddies, part of an audience of black and white soldiers watching a movie, got rushed back to camp one night after "someone passed a remark to someone else." Two black soldiers suffered broken legs.

Curtis, 75, one of five siblings who served in the military during World War II, got out of the Marines after the war and later joined the U.S. Postal Service. He retired in 1984 after 35 years as a mail carrier.

"Hashmark" Johnson

After World War II, America's troop strength dwindled as the nation demobilized. Aftershocks of the war that rocked the world circled around to rock the world at home.

The new social order included a growing black civil rights movement. Jackie Robinson, a black Army veteran who almost had been court-martialed for refusing to sit in the back of a bus during the war, broke major league baseball's color barrier in 1947.

Times were changing. By spring 1948, increasing Cold War tensions with the Soviet bloc convinced President Truman that the United States needed to bring back the draft to bolster its military might. Truman met with black leaders, including A. Philip Randolph, the head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, to build support for his plan.

Randolph turned Truman down flat.

"Mr. President," Randolph said, according to an account of the meeting in Klinkner's book, "after making several trips around the country, I can tell you that the mood among Negroes of this country is that they will never bear arms again until all forms of bias and discrimination are abolished."

"I wish you hadn't made that statement," Truman replied. "I don't like it at all."

The meeting ended abruptly. But the beginning of the end had come for the Jim Crow military.

On July 26, 1948, Truman - possibly due in part to his need for support from black voters in the upcoming presidential election - signed Executive Order No. 9981. It mandated "equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion or national origin."

Truman's order didn't banish Jim Crow overnight. In the first month of 1950, Congress repealed an 1869 law that had required the Army to maintain four all-black regiments. Desegregation of the military was still crawling at a glacier's pace on June 25, 1950, when seven North Korean infantry divisions poured into South Korea. Five days later, Truman ordered U.S. ground forces into the fighting.

at the American Legion 2007

Many of the units, understaffed by more than a third and softened by years of peacetime duty, did not acquit themselves well. Some of the harshest criticism - and the easiest - fell on black units, such as the 24th Infantry. Critics claimed they cut and ran under fire.

Others, including Brig. Gen. Edwin A. Zundel, the inspector general of the U.S. 8th Army, felt racial segregation, not cowardice, was the real culprit.

In Strength for the Fight: A History of Black Americans in the Military author Bernard C. Nalty recounts Zundel's exploration of

the problems that plagued all-black units.

By putting black soldiers in segregated units, Zundel said, the military formed concentrations of men from a group with traditionally low scores on aptitude tests. The reason for those low scores? Poor education, another product of racial segregation. The military eventually broke the vicious circle by distributing black replacements to white units.

Medal of Honor

The problems overshadowed cases of real heroism, such as the

story of Pfc. William Thompson, a member of the 24th Infantry and

one of the first recipients of the Medal of Honor for service in

Korea.

Covering for his platoon as it retreated, Thompson held his position and kept firing his machine gun at the advancing North Koreans until he was killed by a grenade.

Fingerpointing and court-martials, however, continued unabated. Thurgood Marshall, a black lawyer who later became a Supreme Court justice, investigated on behalf of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and 39 soldiers from the 24th Infantry who had been convicted of serious breaches of discipline, including running from the enemy.

Marshall, according to Nalty's book, discovered twice as many blacks as whites faced military tribunals in the Far East Command, even though fewer than one in six soldiers was black. Black officers rarely sat in judgment on court-martials, and black defendants typically received much stiffer punishment than whites for similar offenses.

One black enlisted man had been tried, convicted and sentenced to life in prison in a proceeding that lasted just 42 minutes.

"Even in Mississippi," Marshall said, according to Nalty's book, "a Negro will get a trial longer than 42 minutes, if he is fortunate enough to be brought to trial."

Integration of the military still was a work in progress when the Korean War truce came July 27, 1953. But Curtis' twin brother, Clarence, who also served as an ammunition handler in the Marines during the previous war, got some of the benefits.

Like his brother, Clarence Curtis left the military when World War II ended. A short time later, he joined the Army and then switched to the Air Force. Curtis served two years in Korea, loading aircraft munitions with integrated units in Pusan and Kunsan. He was a technical sergeant when he retired from the Air Force in 1963.

"It was always dangerous," said Curtis, who now lives in Los Angeles. "Sometimes it was scary. But I had no trouble with the guys I worked with. We all got along."

Even as the newly integrated military eased into the Cold War of the 1950s, the race issue heated up at home. Klinkner, whose book explores the convergence of factors that have brought about social change, says desegregation in one area, such as major league baseball or the military, exerted push-and-pull forces in others.

"Black soldiers came home and said, 'Hey, I can fight alongside these guys and eat next to them in the military. How come I can't sit next to them in a restaurant back home?'" Klinkner said.

Changes Come Slowly

Segregation in the United States continued to confound the

military. Blacks stationed at some posts and bases couldn't find

housing near their jobs. Despite their improved status within the

military, black soldiers still had to take a back seat to whites

when they rode on civilian buses. Military leaders, civil rights

activists and others fought for changes that came slowly.

As it had for the United States in Korea, the tide finally turned their way.

Two years after the war, Marshall won another battle against segregation in Brown vs. Board of Education, the Supreme Court case that ended "separate but equal" schools for minorities. On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery, Ala., after refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man. A year later, the Supreme Court declared segregation on buses illegal.

More than 175 years after the American Revolution, the path to full citizenship - albeit one still strewn with many obstacles - had begun to materialize. The dreams of men such as Calvin and Clarence Curtis became a reachable reality for minorities: Along with their paychecks and their training, they finally got their opportunities.

As a young boy growing up on a hardscrabble farm in South Carolina, Lloyd W. "Fig" Newton attended segregated schools and read by the light of a kerosene lamp. In 1956, the great-grandson of slaves joined the Air Force, where he later flew with the Thunderbirds and ultimately became the nation's seventh African-American four-star general.

Newton, who heads the Air Education and Training Command at Randolph AFB, credits the integration of the military during the Korean War for giving blacks and other minorities the chance to succeed.

"We saw that it didn't make any difference who was in the unit for the unit to perform well," said Newton, who plans to retire from the Air Force on June 22. "We learned it didn't make any difference to the enemy which of us died, and we learned that we can't succeed without everyone participating.

"Nothing has changed. America cannot reach its full potential without all of our resources, and people are our most important resource."

This article, by San Antonio Express-News staff writer David Uhler, was reprinted with the permission of the San Antonio Express-News.

Additional Resources

UNCTV interview with Prof. Melton McLaurin, author of The Marines of Montford Point: America's First Black Marines

History of the Congressional Gold Medal

Act of Congress (P.L. 112-59; 125 Stat. 749) authoroizing the Congressional Gold Medal

Remarks by Rep. Charles Rangel about Montford Point Marines

Desegregation of US Marine Corps

Profile of Montford Point Marine William Washington

from KETC television in St. Louis

Make Us Proud: Documentary from

Marine Cpl. Kevin R. Wright

The Marines of Montford Point: Narrated by Louis Gossett, Jr.

Navy and Marine Corps Video News

Item from 15 February 2008

http://www.airsafe.com/wwii/ccurtis.htm -- Revised: 11 November 2017